Between Seeking Michigan (Deaths, 1897-1920) and FamilySearch, Michigan is fortunate to have a robust online presence for vital records research. Factoring in the many outstanding obituary indexes that also exist from across the state, including Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, and Saginaw, researchers have several fantastic online options when looking for a vital record date.

That being said, the post-1920’s are a particularly problematic era for online genealogy research here in Michigan. First, the statewide death records available at Seeking Michigan end with 1920 (with very few exceptions). Second, although many county-level death records have been indexed and are abstracted at FamilySearch in the database “Michigan Deaths and Burials, 1800-1995,” the impressive holdings there are not statewide, and each county does not contain records during that entire two hundred year time period. Finally, although a number of local societies and county clerks’ have placed indexes to their local records online, including Genesee, Macomb, and Washtenaw, that number is still only a small percentage of the state. Thus, researchers are presented with a significant post-1920 online research gap.

Enter the Masons. Each and every year, dating well back into the 1800’s, the Grand Lodge of Michigan of Free & Accepted Masons held an annual meeting in the state to discuss lodge business, finances, news, and local activities. As with other large fraternal societies, such as the Grand Army of the Republic, a published proceeding documenting the annual state gathering soon appeared. Impressive runs of the annual Transactions of the Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of the State of Michigan can be found onsite at several research libraries in the state, including the Library of Michigan and the Bentley Historical Library; digital copies of pre-copyrighted years can also be found online at the HathiTrust web site. Buried within each volume is an “In Memoriam” section, which identifies all of the known members of the Michigan masonic community that died in the previous calendar year. Granted, not everyone’s ancestors were Masons, but a significant number were, as the membership statistics would indicate; the 1936 statewide membership was over 123,000. The potential value of these volumes, particularly in the post-1920 time period, should be readily apparent.

However, the Memoriam section is often challenging for genealogists not familiar with their ancestors’ lodge name or number, as the decedent’s names are sorted by lodge number. With more than 500 lodges in existence across the Upper and Lower Peninsulas, scanning through each lodge’s entry represents a significant time commitment.

To make this important resource more accessible to researchers, I have compiled a master index of the deaths that appear in the volume(s), sorted by last name, and posted a PDF of the file here at my web site: genealogyKris. It is also accessible via the home page from the link along the top: “Mich. Masons: Deaths.” Researchers will find the decedent’s name, death date, lodge name, number, and location in Michigan, all important clues for finding obituaries, death records, and much more. Here is a sample entry:

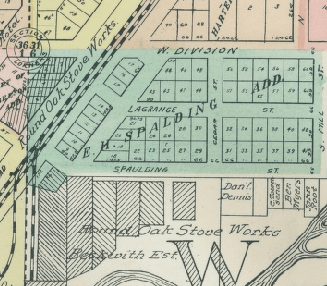

Looking through the Bay City, Detroit, Flint, and Roscommon newspapers around the dates of death should quickly yield obituaries for the men listed in the sample image above.

To date, my site contains more than 2,000 extractions from the 1936 volume, which largely contains 1935 deaths. Additional volumes and years will be added regularly as they are input. Stay tuned!